The Bleu de Travail

Part one: The evolution of a work jacket

If there’s a core signature item at L’Usine Bleue, it’s the classic, French blue workjacket – or overshirt, depending on how you wear it. It goes by many different names – coltin, la blouse, bleu de chauffe. But the most common one is ”Bleu de Travail”, which means ”work blues”. Despite its humble beginnings, the Bleu de Travail is now part of that illustrous club of timeless items, such as the duffel coat, the trenchcoat, the striped breton shirt and the pea coat. Clothes which have long since left the crazy cycle of seasonal fashion.

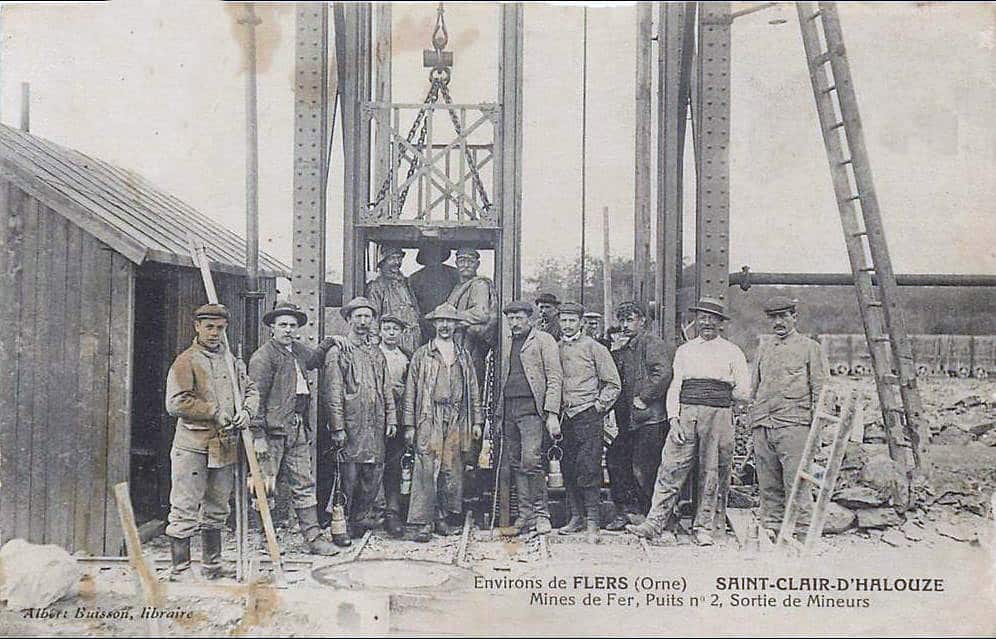

The evolution of workwear is in lockstep with the industrial revolution. Before, most people would wear the same thing at work as they would at home. Indeed, there was little difference between home and work, since most were farmers.

But with the industrial revolution, the demands for specific clothes to wear at work grew. The oldest of workwear, an apron over a belted blouse, just didn’t cut it anymore. The new generation of workwear had to protect the worker, be comfortable and practical to work in, be hardwearing and easy to mend – and not least – be cheap to make.

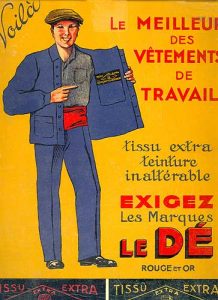

So the apron became an overall or bib pants, which soon separated into pants – and a jacket. At first, workers had to buy their own workwear. But soon, factories began suppling its employees with workwear, which gave rise to another industry – the workwear makers.

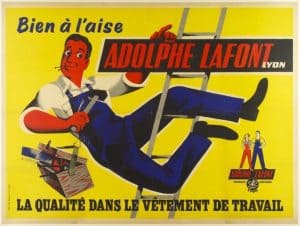

In 1844, Adolphe Lafont is believed to have created the first, standardized Bleu de Travail: An unlined blue cotton moleskin jacket, rounded shirt colar with no lapels, 4-5 front buttons, 2 large front pockets for tools, one breast pocket for note books and tobacco, one inside pocket for personals – all topstitched for easy production. Later they would also be made in cotton twills (essentially jeans) and herringbone twill – all three very sturdy and durable weaves. Lafont’s design was soon copied by other manufacturers all over Europe and with little variation remains the same even to this day.

Even if most industry workers today don’t wear a Bleu de Travail to work, it has become a proud symbol for two centuries of French workers, their hard work and sacrifice.

Part two: Why blue?

The classic Bleu de Travail actually wasn’t blue in the beginning, but rather dark grey or black. Until the 1700s, blue fabric dye was usually made from woad, indigo or the mineral lapis lazuli and very expensive. And for a long time blue was reserved for nobility and royalty.

But around 1704, a new blue dye was discovered by accident by the Berlin laboratory Diesbach and Dippel. Diesbach was one day out of a key component for his famous red. The chemist Dippel suggested a replacement, but this didn’t produce red as expected, but rather a deep, vibrant blue. The new blue became known as Berlin Blue, and Dippel kept the process a secret for ten years until the English chemist John Woodward figured it out and brought it widely to market – now known as Prussian Blue.

This new synthetic blue was much cheaper and easy to maintain. And in the early 1800s, it became the dominant colour for professional clothing, such as uniforms for the military, navy, police, fire fighters and various other corps. Eventually it also became the colour of the growing workforce of industry – and the first versions of the Bleu de Travail were born.

At the turn of the century another blue dye began dominating – the hydron blue. Hydron blue is even cheaper to make and more resistant to wearing, fading and bleaching.

By the 1900s, the Bleu de Travail in hydron blue had become the standard for workwear in France and a part of the identity of the working class. Workers wore blues. Managers and supervisors wore white or black. In the 1960s, many workers began thinking of it as something of a class stigma and the blue started fading from the factory floors.

But in 1968 that changed again, with the student revolts in Paris, where young, middle class students wore the Bleu de Travail to show unity with the working class. The Bleu de Travail became, and remains, a proud and beautiful symbol of the heroes of French industry.

Part 3: Moleskin

The classic French workjacket, the Bleu de Travail, was a product of the growing demand for practical, comfortable, long-lasting and cheap workwear in French industry during the 1800s.

These clothes were made from hardwearing fabrics, like cotton twill, cotton drill and corduroy. But the most iconic fabric used, and what is probably these days most closely associated with the Bleu de Travail, is MOLESKIN.

Moleskin is a ”fustian” – a ancient class of fabrics that is thought to have been first produced in Egypt during the Roman empire. Fustians, such as corduroy and velveteen, are characterized by their much greater number of weft threads, which makes them very strong, durable and also warm due to the nap (like a thin fur almost) on the fabric’s surface.

The easiest way to describe a cotton moleskin is as a shaved corduroy, and it was in fact originally simply an uncut corduroy. But ”modern” moleskins use a form of sateen weave, which allows for a unusually large number of thick weft threads (crosswise) to be very tightly inserted between the warp threads (lengthwise). This creates an incredibly closely woven, dense fabric. It is then brushed on the back to raise a furry nap, which is sheared to create a soft, very smooth, and suede-like finish. Some found it to resemble the fur of a mole, hence the name.

Moleskin is in many ways the perfect workwear material. It is so tightly woven that it’s virtually windproof, some versions even rainproof. Many farmers preferred moleskin since the sharp hairs of farm animal couldn’t poke through the clothes and welders used them, since welding sparks would simply bounce off. Moleskin is also unsually warm relative to its thickness, but can still breathe – making it usable all year round. It has very low friction, which reduces wear and ”swish” (moleskin is still a popular material for hunting clothes since its so quiet and it is also used in anti-abrasive bandages.) And not least, it’s extraordinarily hard-wearing – which is why vintage moleskin Bleu de Travails are often found in such good shape, despite years of everyday use.

Moleskin is in many ways the perfect workwear material. It is so tightly woven that it’s virtually windproof, some versions even rainproof. Many farmers preferred moleskin since the sharp hairs of farm animal couldn’t poke through the clothes and welders used them, since welding sparks would simply bounce off. Moleskin is also unsually warm relative to its thickness, but can still breathe – making it usable all year round. It has very low friction, which reduces wear and ”swish” (moleskin is still a popular material for hunting clothes since its so quiet and it is also used in anti-abrasive bandages.) And not least, it’s extraordinarily hard-wearing – which is why vintage moleskin Bleu de Travails are often found in such good shape, despite years of everyday use.

Adolphe Lafont was arguably the first manufacturer of a moleskin Bleu de Travail as we know it today, and since the mid to late 1800s the model has remained much the same – unlined, buttoned front, single-button cuffs, 4 pockets and a slightly curved collar (col chevalière).

Moleskin is sometimes referred to as the ”French denim”, which is a bit of a misnomer, since denim is also French. We’re of course no entirely impartial here, but we think denim should actually be referred to as ”American moleskin”.

Traditionally made from hardy cotton drill or moleskin, this jacket could withstand the tough demands of physical jobs, and any holes were simply patched up with other pieces of cotton. Loose in fit, it could be worn as a protective layer over other clothes, with buttons up the front and at the sleeve to allow for rolling, as well as three or four patch pockets for storing small tools and loose parts. While early iterations were not labelled, certain brands started purpose-making them in the early to mid 20th century, including Vetra and Le Laboureur, which still operate as workwear brands today.

Traditionally made from hardy cotton drill or moleskin, this jacket could withstand the tough demands of physical jobs, and any holes were simply patched up with other pieces of cotton. Loose in fit, it could be worn as a protective layer over other clothes, with buttons up the front and at the sleeve to allow for rolling, as well as three or four patch pockets for storing small tools and loose parts. While early iterations were not labelled, certain brands started purpose-making them in the early to mid 20th century, including Vetra and Le Laboureur, which still operate as workwear brands today.